Get a short history on the neighborhood and how its evolving

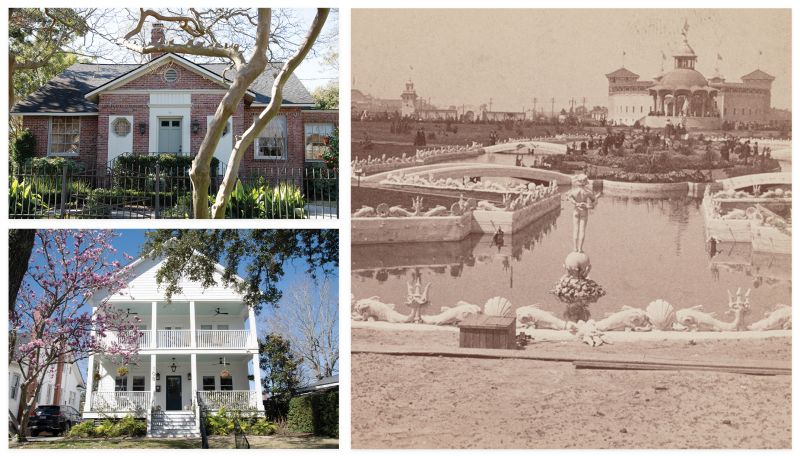

(Clockwise from bottom left) Homes in the Wagener Terrace neighborhood; the Inter-State and West Indian Exposition, circa 1902.

Last year, I moved here from Washington, DC, spending the academic year teaching College of Charleston students how to think and write about “place” while finishing a book for National Geographic. It’s been a treat. My students are inquisitive, and my colleagues collegial. The city is radiant, especially during the golden hour as the glint bounces off the Ashley to gild the low-slung skyline. In this political season of red meat and white-hot blather, Charleston’s pleasures—from food to architecture—have been both welcoming and mercifully bipartisan.

Last summer, I quickly found a rental in Wagener Terrace and established new routines. I shopped at the Food Lion and discovered the sweetness of South Carolina peaches. I learned that Ethan at Herd Provisions stirs a perfect gin martini, and if he’s not on duty, his assistant Reese is just as capable. Neighbors were welcoming. “It’s a good day when your feet hit the ground,” avowed a cheery 80-something wheeling her blue recycling bin back into her garage as I walked past. There was whimsy: Someone parked a Deux Chevaux in their driveway and christened the French subcompact “Dolly.” And desire: A house for sale on St. Margaret Street—gleaming white with black trim, a one-car garage, and fringed by a phalanx of palmettos along the horizontal slatted fence—caught my eye. Was it worth considering? Zillow had it listed at $2.6 million; the monthly note: $20,312. Definitely above my pay grade, but not someone else’s.

(Left) Hampton Park; (Right) Greater St. Luke AME Church.

Being a travel writer, I seek out the stories behind neighborhoods. It’s both my job and my hobby. Wagener Terrace is no exception. It was once part of the colonial Gibbes Plantation where Redcoats landed in 1780. A decade or so later, the South Carolina Jockey Club opened a racetrack here, and 1865 saw the nation’s first Memorial Day, inaugurated by formerly enslaved Americans to honor the Union troops who emancipated them. In 1901, it became the site of the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition, a World’s Fair lite that drew Teddy Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and Booker T. Washington. It proved a grand party, but a commercial flop. Eventually a chunk of the fairgrounds became Hampton Park, where I walk daily, circumnavigating the ghost of the old racetrack (now Mary Murray Drive) and colonnades of immense magnolias and mossy live oaks guarded by a ragtag gang of Muscovy ducks. Aside from New Orleans’ St. Charles Avenue, I can’t think of another Southern promenade as glorious in its shady beauty.

Plaited in 1919, the community of Wagener Terrace—named for Captain F.W. Wagener, a German-born wholesale grocer who owned what is now the Lowndes Grove wedding venue—was developed in the 1930s and ’40s with a range of housing from small bungalows to brick colonials. Many of the buyers were Jewish and Greek families in the first flush of material success. In 1955, neighbors built a synagogue on Gordon Street. By the 1970s, suburban migration transformed the neighborhood into a haven for middle-class African Americans, who found they could buy into the American dream of a handsome house and tree-shaded yard, with a lovely park to boot. The synagogue became Greater St. Luke’s, an African Methodist Episcopal Church, which it remains.

At the start of the 21st century, many older homeowners began to sell to a younger generation. These newcomers weren’t stratified by race or religion, but by degree. College-educated professionals—doctors, lawyers, and professors—began to supplant earlier arrivals. Driveways that used to contain Buicks and Fords now hosted Audis and Teslas. At first glance, Wagener Terrace was not out of place with other older American neighborhoods undergoing an evolution familiar in Cincinnati, Little Rock, or Tucson. But like a king tide on a sunny day, a flood of outside money began a silent rise. The surge began changing things.

Charleston isn’t my first boom town. I lived in San Francisco during the dot-com frenzy and witnessed Marfa’s flowering as the Best Little Arts Town in Texas, as well as New Orleans’ optimistic revival after Katrina. If city futures were a market, I’d have gotten rich.

Meanwhile, my neighbors and I speculated about the St. Margaret house. “Who would buy it?” Then, in November, someone did, one-car garage and all. (Zillow’s recorded sale price: $2.5 million). Other houses continued to turn the color of Domino sugar cubes, bleached to Instagramable perfection by their designers. Walking to Herd recently, I saw a Mercedes SUV with Florida plates idling outside a whitewashed duplex ($1.67 million) waiting for the Realtor, I reckoned, and willing to pay seven figures to feed the ducks in Hampton Park.

You may wince, or perhaps shout “bravo,” but I learned long ago that with cities, change is inevitable. Neighborhoods are in constant flux. Families move out and in. Houses are enlarged or updated. Fairs close and racetracks vanish. Like one of the neighborhood’s grand live oaks, each year records another ring of the community’s history. Nothing stays the same. Now, the gentrifiers of 2010 are themselves being gentrified. (Though they can always sell at a tidy profit.) If it feels unsettling to live in a neighborhood that gets a little less South and a little more Southampton every year, remember this: What goes up can come down, too.

Andrew Nelson’s book Here Not There will be published this month by National Geographic Books.